It’s not you, it’s the startup life.

It’s not just founders struggling with burnout, depression or mental health at startups. I should know. It happened to me.

My startup story starts in Loveland, Colorado. I had shimmed my degree in electronic media into a project management position at a fast-growing, then fast-failing company. Founded by a dot com success story, the company sold educational resources to aspiring entrepreneurs.

It was my first taste of the entrepreneurial adventure. I loved the fast pace, experimental nature and rollercoaster descents of fast success. My years there were also littered with dysfunction (a fair share my own), poor leadership and management. Eventually that company’s growth bubble burst and I was laid off alongside a large number of colleagues.

It was during that role that I first learned of the burgeoning Boulder startup scene. I cultivated an obsession over startuppers’ Twitter feeds, devoured episodes of Techstars’ “The Founders” and I was soon making regular trips to attend Ignites, meetups, and the first Boulder Startup Week.

I made the leap and relocated to Boulder. My goal was to continue consulting and to network in hopes of find a community manager job at a proprietary tech startup within a year.

My first Tuesday as a Boulder resident I attended #BOCC, the weekly startup coffee meetup. I introduced myself as new to town and said I was looking for a community manager role at a startup.

Two weeks later I met the co-founders of what would become my first real startup role. We chatted for roughly 90 minutes. I listened far more than I talked. The technology behind what they were building was fascinating. They oozed passion and excitement for where they would go next. I had never thought I would work around such wildly intelligent, innovative, driven people.

When we met a little over a week later, I was handed an offer letter. When they asked if I had questions for them I was so dumbfounded by my grand strike of luck (only two weeks to find my dream job!) I said nothing. I had no idea of what I would actually even be doing. But it didn’t matter. It was happening. I was going to work at a real, bonafide startup.

My start date was set for two weeks later. The night before I began one of the co-founders emailed me to ask me if I had a computer and could I bring it with me the next day. I found it a little odd, but brushed it off as a byproduct of moving fast.

The first few weeks were a blur. I was the first non-engineer at the company, as well as the first woman. I told myself I was up for the challenge. We were building something! We were moving fast! I was tough. I was blazing trails for the women who would come after me. I eschewed pangs of confusion and uncertainty as the normal feeling of inadequacy you get at any new role. I didn’t dare share with anyone that I had no idea what I was ultimately responsible for, what would count as a win in my role, or even what expectations of me were.

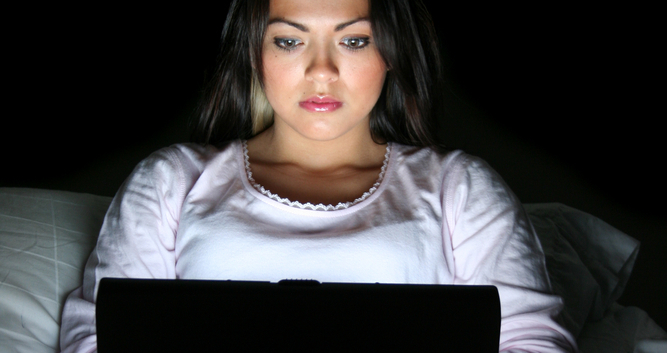

I attempted to subdue those fears by working a lot. A lot. There were nights when I would ride my bike home at 9 p.m. or 10 p.m., only to open my laptop again and continue working after I got home. I spent time over weekends logged in making sure our help desk was empty or in the office trying to finish the project I hoped would make me feel secure there. I would kill my alarm and open my email with one swift motion each morning. I still couldn’t really explain what I was doing. Or what my role was.

Around six months after I started the founders called me into the conference room. Certain that I was getting fired, I had to put my hands under the table so they couldn’t see them shaking. They told me they were happy with me and gave me a raise. I left feeling more confused than ever. I felt like a failure day in and day out coming to the office. But people who are failing don’t get raises, right?

It wasn’t long until I was retreating from the office to cry in the bathroom two to three times a week. While there were specific instances warranting tears, more often I cried out of a potent blend of overwhelm: a fear of not knowing what would happen next, what I was supposed to be doing, the weight of being the empathetic ear in an environment where other people were struggling. I was barely carrying my own burdens and I was adding others’ by the day.

During this time I was also very involved in the startup community around Boulder. I was a die hard regular at #BOCC, attended Ignite, helped organize events for Boulder Startup Week, and made regular appearances at a litany of other startup and tech events. If you met me during this time, you would have never known how awful I truly felt. I regularly espoused how amazing things were. How excited and grateful I was for my job. How wonderful it was to be a proxy to what the engineers I worked with were building. Sure the hours were long and things felt cobbled together, but startup life, right? Work hard, play hard! I dare not confide that it had been months since I had experienced play, let alone rest.

Not only was I not confiding in anyone, I was in outright denial. My (now) husband and I were living together. My laptop, iPad, or phone were a consistent third wheel. I would complain about stress or talk about dysfunction at work but would get angry or resentful if he were to suggest perhaps I find something else. Or that the job was taking a toll on my well-being and our relationship. Recently engaged, I invited both families to our house for Thanksgiving dinner, our first blended family event. I cooked a full Thanksgiving meal in between furious and panicked typing at my computer as something exploded at work. Our families introduced themselves to each other. I barely stopped responding to emails for 30 minutes to eat. My husband did the dishes.

At 3 a.m., 364 days after I had started at the company, my husband was awoken by the light of my iPhone as I panickedly check for emails I wasn’t even expecting but could possibly be coming. I couldn’t miss anything. I would fail. I would get fired. People would know. I would be nothing. I started crying and pacing the room insanely and I couldn’t stop. I could no longer deny that something was wrong.

My husband convinced me to stay home from work the next day and see my doctor. I left her office with prescriptions for antidepressants and a fast-acting anti-anxiety medication. I took my first pills a few hours after the appointment. As the anti-anxiety medication set in, my heart and mind slowed for the first time in months. I felt a calm set in that I hadn’t felt in a year. My head came up from under the waves. I hadn’t even known I was underwater. I had been drowning and never noticed I was wet.

The next day, my 365th, I resigned my position. I began seeing a therapist twice a week. Under her and my doctor’s guidance, I took antidepressants as prescribed for over a year. The therapist guided me through looking at my experience, my feelings of (un)worthiness, my relationship to work. What I originally had thought was a long hard road to feeling normal took less than a month. I never refilled the anti-anxiety medication again.

It’s been more than five years since I left that company. I’ve worked in and around nothing but startups in the years since. I don’t have a perfect track record of mental health (we’ll save the bramble patch that is post-partum for another day), but I’ve never woken at 3 a.m. to check my email since. It can wait. And it’s not worth it.

At first, I was extremely sheepish of sharing my story with others. I shared the full truth with only a few select friends. I made excuses to almost everyone else. I carried the weight of embarrassment and shame. Then slowly I started trusting and sharing more of the truth with fellow startup friends. Behind closed doors, in hushed tones over coffees, friends in turn related their similar experiences to me. They had tumbled down the rabbit hole in pursuit of the startup life too.

There’s been a promising turnaround in the story of startups and mental health during the last few years as first investors, then founders, have begun to share their struggles with depression, burnout and mental health challenges faced in the startup world. Popular articles around the high stakes of entrepreneurship have helped to bring awareness to the issue. This ongoing conversation is a wonderful development, but the conversation still skews heavily male, heavily white, heavily financially successful, and heavily those in leadership positions.

The challenges and burdens of the startup life extend far beyond these demographics and the board room. Startup team members’ struggles with depression and mental health are just as worthy of attention and care. Team members need to be included in these discussions, in research projects, and in awareness efforts. These challenges do not discriminate.

I hope investors, board members, and mentors will consider their role in this cycle. Just as it is being expressed that no company is worth a founder’s life, I hope you can express the same is true for their team members. Most importantly to founders and leadership who set the tone and culture for teams.

If you are at a startup and struggling, first and foremost: You are not alone. You are not crazy. You are not a failure. The demands of the startup life can be unrealistic and unrelenting, not to mention not worth it. It’s OK to decide that an environment or expectation is not right for you. There are startups that are healthy, caring, professional (not a dirty word!), sane environments and they’re probably hiring talented people just like you.

Just as the narrative is moving away from glamorizing the founder experience, let’s do the same for team members working at startups. Working at startups can be incredibly challenging for everyone. It is OK to need time off and away from your phones and devices. It is OK to want functioning, adult, professional leadership. It is OK to want a clear understanding of the expectations of you and to communicate your expectations of your employer in return. It is OK to tell people that your startup is hard or dysfunctional or that working there really sucks right now. It is OK to leave and find something that is a better fit for you. You don’t have to sacrifice yourself to be valuable.

My story isn’t really unique to startups. Startup culture propagates a story: normal jobs are boring. Startups are exciting and different. Startup people are extraordinary and special. Working at a startup allows you to have a bigger impact on the world. Working at a startup can be more fulfilling than traditional work.

I was drawn to the startup life with dangerous baggage: a deep-rooted belief that I was unworthy. I grabbed hold and clenched my fists around the startup life story determined to wrest my own postscript: if I startup hard enough, a startup will fulfill and validate me as a human being.

I wasn’t waking up at 3 a.m. to check emails because I was worried I would get fired. I was waking up at 3 a.m. to check emails because I didn’t believe that at my human core, I was enough. This is not unique. Our society and culture are addicted to defining our sense of worth from work. Startups merely accelerate and exacerbate this toxic and dangerous belief system.

After sharing an early draft of this post with my colleagues, Jerry Colonna gently pointed out to me that if we bring our suffering to work and try to use the work to stop our suffering, we run the risk of turning work into a form of violence, regardless of whether or not we work at a startup or have power over another. It was a shattering insight. My painful experience undoubtedly reverberated in those around me.

Today I work at a startup that works with startup leaders to end what Jerry refers to as violence in the workplace. Violence is his word for the emotional turmoil and turbulence that I, and so many, have experienced. Reboot is the most adult, caring, empowering, and effective professional environment I have ever been in. I accomplish more high-quality work in less hours than I ever have before. It’s not perfect (spoiler alert: nothing is) and I have cried there, but tears and struggles have been met by empathetic and curious colleagues who have been willing to walk into issues and challenges with me as opposed to brushing them under the keg. It is what Reboot inspiration David Whyte calls, “Good work, done well, for the right reasons.”

This doesn’t need to be a unique experience. If there is anything I have learned from my experience in startups, it’s that if something is deemed valuable enough, enough of a priority, it will be. I can’t think of anything more worthy than this.